Mila Magnani was 15 years old when she started to grow a beard. Aside from her classmates’ mockery, she wasn’t too alarmed. “Kids are mean,” she says. “I just thought I had the hairy Italian gene.” At first, the hair growth was light, like an adolescent boy’s peach fuzz. But when a mustache sprouted on her upper lip, her concerns poked through as well. “I saw that my younger brother had less facial hair than me, and that’s when I finally got so bothered by this that I went to seek the care of a doctor.”

There, Magnani mentioned other symptoms she’d been experiencing since the age of 12. Her skin was breaking out—normal, she knew, for her age—but she was also feeling tired all the time, having intense food cravings, experiencing painful, irregular periods, and waking up drenched in the kind of sweats usually associated with menopause, not puberty.

Her doctor put her on a birth-control pill. The acne cleared, and her periods grew regular, but Magnani knew something was still off. She went back to her doctor. He prescribed a Mirena IUD—the kind that releases hormones into the uterus—and told her everything was fine.

But she was not fine, particularly during her first year at New York University, when the pandemic hit. She sought out more doctors, more labs, more opinions. “They all told me that I was completely normal … that my symptoms were frankly just part of being a woman.” One doctor prescribed antidepressants. Magnani knew her problems weren’t, as the doctor suggested, “all in her head.” She didn’t take the pills. She visited more specialists, had an endoscopy, then a colonoscopy, then a consultation with a surgeon who wanted to slice her open on his table right there and then.

“I was burning through my savings,” says Magnani, 22, who is now a model and TikTok influencer.

After spending six months on a waiting list for an appointment with an endocrinologist in Texas who’d come highly recommended, she flew from New York to meet with him. “He told me, ‘You’re just in my office because you got fat.... If you’re upset that this is part of being a woman, you have to learn that these are your genetics and this is just how your body is.’”

“I saw that my younger brother had less facial hair than me, and that’s when I finally got so bothered by this that I went to seek the care of a doctor.”

Confused, broke, bloated, and fed up, both with being dismissed by doctors and with the American for-profit medical system, Magnani lost hope. Taking advantage of her French citizenship to access the country’s free health care, she left New York and moved to Paris, determined to figure out why her body was not functioning the way it should. Then, six years after first investigating her ongoing symptoms, she was diagnosed by a French physician with polycystic-ovary syndrome (PCOS).

PCOS is a common, clinical syndrome defined by irregular periods, anovulatory cycles (menstruation without ovulation), and numerous small cysts around the periphery of the ovary. Signs of excess androgen (“male” sex hormones that women have in small amounts) can be present, as well as hirsutism (coarse hair on the face or body), hair loss from the scalp, and acne. It is often associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance (when cells in your muscles, fat, and liver can’t use glucose from your blood for energy), obesity, cholesterol disorders, and cardiovascular disease. PCOS can lead to fertility challenges, and, if left untreated, it can also increase the risk for uterine cancer. Though women with PCOS are born with the syndrome, they are usually asymptomatic until puberty. Sometimes it makes itself known later, in a woman’s early 20s.

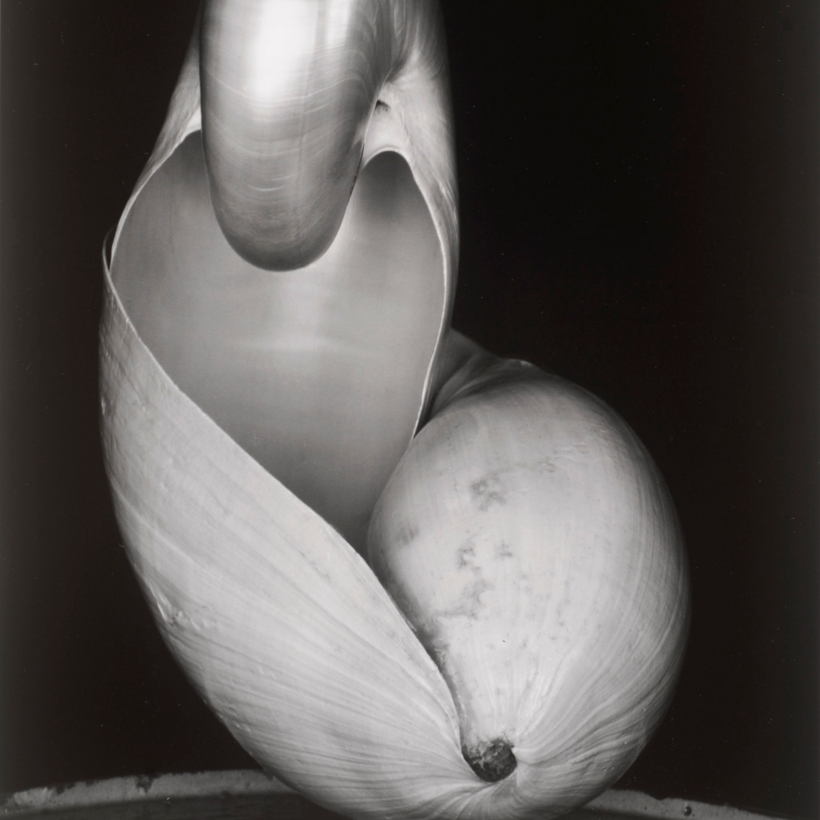

But a doctor doesn’t need to note most of the symptoms of PCOS to diagnose a patient with it. “The usual way that we make the diagnosis is you have to have two out of the three criteria,” says Dr. Elise Brett, an associate clinical professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York, and a board-certified endocrinologist. “You either have to have irregular periods, classic signs of polycystic ovaries on the ultrasound”—a pearl-like ring of cysts—“or clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism.” Women with atypical PCOS don’t have issues with weight or insulin resistance.

“It’s a very broad spectrum,” says Dr. Jessica Berger-Weiss, a gynecologist in Bethesda, Maryland. “Some doctors are just like, ‘If you’re not heavy, then you can’t have PCOS.’ And of course that’s not true.”

Brett’s PCOS patients often arrive in her office frustrated and confused after years of being unheard by their doctors. “A lot of times [patients] have been to their gynecologist, they’ve been to their internist, they don’t have a diagnosis.” And yet, PCOS is “extremely common,” she says. “Up to 10 percent of women have the syndrome.”

As with many things related to women’s health, ignorance has been the main barrier to treatment. “In the largest study of PCOS diagnosis experiences, many women reported delayed diagnosis and inadequate information,” concluded a research study published in 2016 in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“A lot of times [patients] have been to their gynecologist, they’ve been to their internist, they don’t have a diagnosis.”

With so much medical ignorance surrounding the syndrome, it can take years or decades for women to get answers. Berger-Weiss says she diagnoses women in their late 30s, 40s, or even on the brink of menopause with PCOS. “Sometimes they’re like, ‘Well, now everything makes sense.’”

While PCOS is not curable, its symptoms are treatable with medications. “The way we treat it depends on what the patient’s concerns are,” explains Brett. Treatments commonly include birth-control pills, to make sure the uterine lining is shedding; spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic that also blocks androgen receptors and testosterone; and metformin, a Type 2 diabetes drug used to treat PCOS’s metabolic issues. “Once someone is actually diagnosed, the standard management options are often very helpful, and there is a range of medications and interventions,” says Berger-Weiss.

Many PCOS patients who see Berger-Weiss come in with “concerns that something does not seem right” or “feel that their body is off-balance in some way.” Some women who feel off but don’t have a diagnosis seem to be resorting to the Internet and social-media hashtags for answers. Plug in #PCOS on TikTok and thousands of videos pop up, created by doctors and by patients. Some of Magnani’s videos on the issue have millions of views.

As with all social media, the platform is full of people spouting dubious advice. One TikToker recommends various supplements, coffee, and gluten-free cookies. Another claims that switching from cardio to Pilates will cure it. And many offer a laundry list of holistic approaches, such as reading the right book or ingesting the right herbs, without any relevant data to back up their claims. The one upside is that the more #PCOS hashtags that appear, the greater the chances that someone who’s undiagnosed but suffering might recognize her symptoms and seek care.

Magnani intends to stay in Paris, working as a model. After years of suffering with PCOS symptoms, she’s largely tamed them. There’s one small upside to the whole frustrating experience: she plans to pursue a degree in either functional medicine or naturopathy. “I was the one who had to figure this out,” she says, and she hopes to save others from the discomfort of the ordeal.

Deborah Copaken is a contributing writer for The Atlantic, a screenwriter, and the author of several books, including Ladyparts: A Memoir and Shutterbabe: Adventures in Love and War. You can read her Substack here