There is nowhere in London like Notting Hill, the stuccoed district that only 50 years ago was a byword for squats and squalor—now more readily associated with Hugh Grant’s foppish charm and pastel-colored, Instagram-friendly, multi-million-dollar houses. And there’s nothing like Notting Hill Carnival either, when more than two million people jam themselves into the narrow streets and squares of W10 and W11 in the biggest celebration of Caribbean culture outside of the actual Caribbean.

While the carnival shares the same bacchanalian energy as New Orleans’s Mardi Gras festival, it has a vital role in the wider inquiry as to what, exactly, constitutes British cultural life. To its detractors, it’s a long weekend of taxpayer-funded anarchy in one of the country’s swishest postcodes. To its many participants and fans, it’s a model of joyful inclusion and an exemplar of Britain’s postwar diversity. For some of my friends, it’s the highlight of their year.

But now for an embarrassing confession: I’ve never really enjoyed myself at the carnival. If this makes me sound less like an authentic Londoner, it’s not for lack of trying. Nearly every August bank holiday throughout my 20s, I shuttled between the deafening sound systems that spring up on every street, losing phone reception, misplacing my friends, before, inevitably, staying up far too late at an after-party and then careering back through the trash-strewn streets to South London. So this year, on assignment for Air Mail, I approached the carnival with some trepidation.

On Monday, after the family-focused events of the weekend, comes Adults Day. I ambled toward the Grand Union Canal with Paul Cox, this piece’s illustrator, who also happens to be my girlfriend’s father. The police presence was immense, with dozens of officers eyeballing the revelers as they marched through metal-detecting knife arches. We spotted a young man being handcuffed, his sheathed blade lying on the pavement, just one of the 275 arrests made over the course of the carnival.

The flip side to the sound of the carnival is the fury of some of its participants. Since 1987, there have been six murders, and the policing operation to stop that tally from ticking up costs more than $11 million a year. This year the Metropolitan Police reported eight stabbings.

The thorny relationship between the police, the local community, and violence was central to the creation of the carnival. In the postwar years, white working-class Teddy boys—with greased-back hair and drape jackets—menaced the Black families who moved into the area from the former colonies of the British Empire, resulting in full-blown race riots in 1958. The following year, Claudia Jones, a Communist, feminist, and Black nationalist, looked to “wash the taste” of the riots out of Notting Hill’s mouth by organizing a Mardi Gras–based carnival in St. Pancras Town Hall, in central London.

The flip side to the sound of the carnival is the fury of some of its participants.

But just four months after this first attempt at a carnival, an aspiring lawyer called Kelso Cochrane, who was born in Antigua, was stabbed and killed by three white youths in Notting Hill. His murder, still unsolved today, inspired Rhaune Laslett to try to bring the community together, with an English-style fête in the neighborhood in 1966. That year, 1,000 people attended. It’s now the world’s largest street party outside of Rio de Janiero.

Arriving on Ladbroke Grove, I watched as an old friend, carefully holding a beer, plucked his baby out of a stroller. The music is mind-bendingly loud, and the sun suddenly frees itself from the cloud. It takes us 45 minutes to move 1,000 feet down the Westbourne Park Road, hemmed in on either side by the crowds following the floats that inch along the tarmac, blasting soca—a mix of African and East Indian music—from their speakers. Nearly everyone around us is in their 20s or their teens, and on occasion they will split into couples and grind, for 30 seconds or so, the men thrusting into the gyrating hips of the women. It’s pretty much sex with clothes on, and it’s curiously surreal to be mobbed by frotting teenagers alongside Paul, who, I should remind you, is my girlfriend’s father.

We decide to head to the Cow, the fashionable pub owned by Tom Conran, the son of legendary design guru Terence Conran. It is known for its excellent Guinness and oysters and is the favorite of David Beckham, who lives nearby and is a surprisingly frequent presence on the uncomfortable wooden benches inside. (He likes it so much he once took Tom Cruise there.)

However, upon arrival we find that it is boarded up—I later discover that they are having the floor replaced. Coincidence or careful timing? Many of Notting Hill’s more tony inhabitants—and businesses—choose to forgo the phenomenal foot traffic of the carnival in favor of a more peaceful, long-weekend holiday. In what might be seen as a conciliatory gesture, a giant Jamaican flag swirls above the pub.

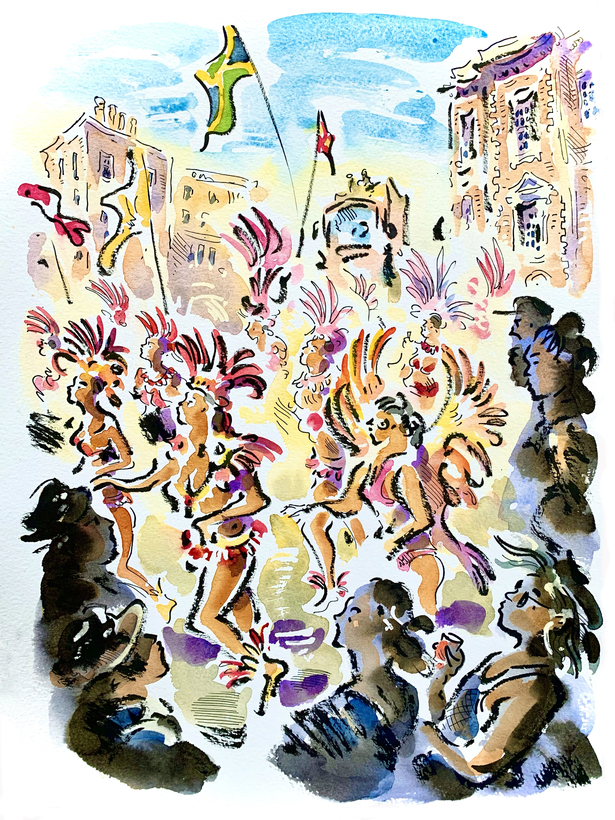

On Talbot Road, we get a prime view of the Mas bands—short for masquerade bands. This is the predominant form of the carnival, originating in the Caribbean, where slaves would mock their masters, who could manage only the stiff “1-2-3” of the waltz. The bands march by in spectacular costumes: D Riddim Tribe. People’s World. Bacchanalia. Pure Lime. One man twirls in gold lamé roller skates, a feathered headdress, and a silver thong, while spooning curried goat into his mouth. He executes a perfect little pirouette while waiting for the parade to re-start.

Traveling through the sound-system stages, a Jamaican feature of the carnival, we head to the Westway—a grim elevated highway—where smoke from the many grills curls into the air. A tribute to Sinéad O’Connor from 10 Foot, who has replaced Banksy as Britain’s most beloved graffiti artist, is painted starkly across the concrete edge of the road. The smell of skunk is thick in the air as we walk up the Portobello Road and across to Elgin Crescent, then back up to Notting Hill Gate.

And for the first time in my carnival-going life I’ve had a hell of a good time. Rather than desperately seeking fun, as I did in my youth, I have stood back and let the fun wash over me. In a city that grows ever more expensive, the Notting Hill Carnival offers a free party to anyone who wants to turn up.

I’m not sure how much longer it will be allowed to continue in its current format. There are agitations to move the event to Hyde Park, where it could be more easily policed. But the carnival’s chaos is an essential part of the whole experience, and will hopefully continue in Notting Hill for many years to come. As for me, if I want to have a really good time at the carnival in the future, I intend to go with my girlfriend’s father.

Charlie Baker is the editor of The Fence magazine