A remarkable set of photographs were recently on display at the new Horse gallery in Dublin for only the second time across the 60 years of their existence. They were taken by Julian Lloyd, who, for most of those years, was looking after Thoroughbred racehorses on stud farms in the Counties Dublin and Meath. In the dynamic horse culture of Ireland, he is known, most recently, for having reared a gray mare called Alpinista, last year’s winner of the biggest race in the calendar, the Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, in Paris.

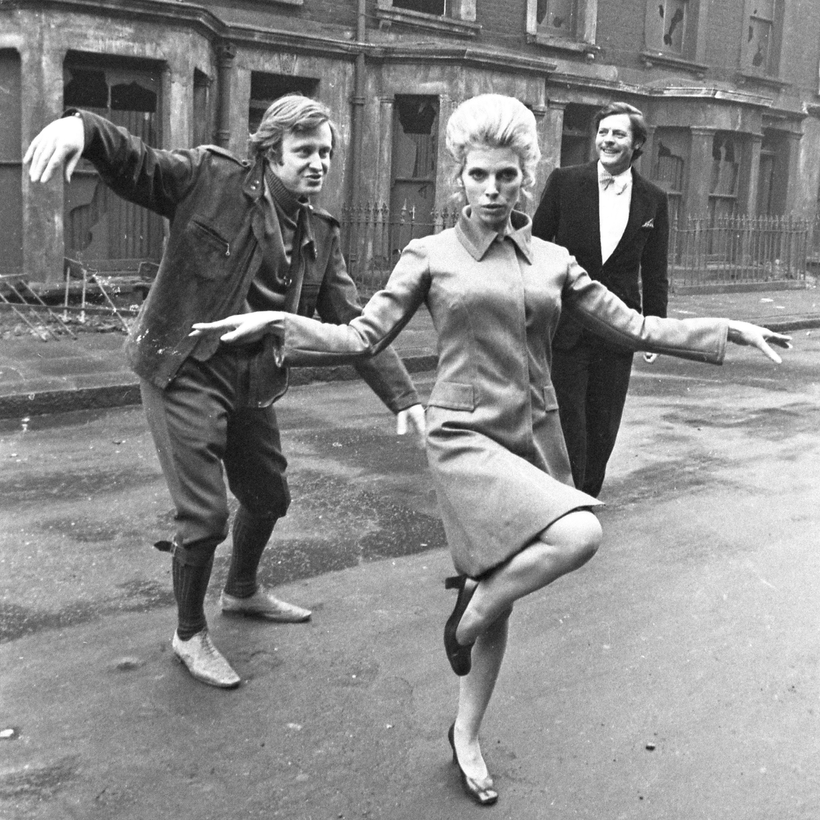

These photographs, which Lloyd started taking in his teens, not only reveal a gifted photographer, barely known or exhibited before. They also document a long-vanished but highly potent subculture: the marriage of rock ’n’ roll, the arts, and “society”—the period that rocked the establishment and gave us the Swinging 60s.

His pictures have an Irish bias—as they would, because Lloyd lived in Ireland—but almost everyone turned up eventually in Lloyd’s domain of horses and castle ruins and eccentric aristocrats and song collectors with a thirst, as well as actors, priests, bards, horse dealers, and J. P. Donleavy. Jerry Lee Lewis, Bo Diddley, Marianne Faithfull, John Hurt, the Stones—they came to Dublin in that era for one reason or another (to record, to party), and Lloyd knew, and photographed, them all.

If horses were one of his preoccupations, music was another—“music” meaning rock ’n’ roll and its tributaries. He already had form and pedigree in the 60s London scene. After boarding schools, including Eton, he took some journalism jobs, reporting and photographing. By 1966 he was working as a photographer’s assistant in the famous Pheasantry building of studios and apartments on the King’s Road, which housed Eric Clapton and others, including David Litvinoff, the sharp-tongued connector to the gangster world for the Nicolas Roeg film Performance.

“You weren’t really a part of the 60s,” the actor Peter Eyre once told me, “if you weren’t at Tara Browne’s 21st birthday party.” Browne was a Guinness heir, youngest son of Lord Dominick Browne and Oonagh Guinness. He was evolved, rich, and connected enough to fly the Lovin’ Spoonful over to play at the family’s Eden-like estate, Luggala, in Wicklow, in 1966. It was an almost revolutionary act. Guests were flown in. There the acid-tripping Brian Jones and others met with many titled and ruined aristocrats. Tara Browne was killed shortly afterward in a car crash in London, as the Beatles reported in their song “A Day in the Life”: I read the news today, oh boy …

“You weren’t really a part of the 60s if you weren’t at Tara Browne’s 21st birthday party.”

But maybe the real test of your membership came a year earlier, in 1965. The agents for all this mixing and flouting of debutante rigidity were the Ormsby-Gore sisters, Jane, Victoria, and Alice—daughters of Anglo-Irish David Ormsby-Gore, fifth Baron Harlech, U.K. ambassador to the U.S. during the Kennedy administration, and, later, Jackie Kennedy’s suitor. They seemed to be able to genuinely float free of class demarcations and move between the new world of classlessness and glamour that David Bailey caught in his Box of Pin-Ups, with its mix of gangsters and filmmakers and gypsy barons, which hadn’t been known before.

Jane, the eldest, was later caught by a sharp-eyed Express photographer suckling her baby in the crowd that came to Caernarfon Castle to watch the present King’s investiture as Prince of Wales, in July 1969. Alice, the youngest, was Eric Clapton’s girlfriend for five years from 1969.

Victoria’s party that year, 1965, was designed by David Mlinaric—an early gig for the most famous of 60s decorators. Most rock ’n’ roll royalty was there, mixing with would-be hippies and Cabinet ministers and peers. Lord Harlech was back from Washington, having unsuccessfully proposed to Jackie, and back in the House of Lords. And there were the key male counterparts of the counterculture, who held the new classless affinities together: Christopher Gibbs, the writer and decorator; Sir Mark Palmer, godson and page of honor to the Queen; and Michael Rainey, owner of the King’s Road clothing shop Hung on You. It was the turning point—the moment that signaled change.

Julian wasn’t at either party, though some of the guests would be in his photographs later. But in 1972, he married the party honoree, Victoria Ormsby-Gore. His best man was Litvinoff.

The Horse Bug

It was Mark Palmer, the Queen’s page, who first took to the road in the “carts,” as they called the gypsy caravans. One of Lloyd’s pictures from the period shows Palmer, the original gypsy baron, standing upright on his cart driving to Appleby Horse Fair, the ancient Gypsy-and-Traveller convention. (Gypsies: English and Scottish; Travellers: Welsh and Irish.)

Lloyd and his new wife got the horse bug, too, and took to the road, traveling with the carts. He applied for a job in Ireland to work at a Thoroughbred stud farm. He had a brief period training racehorses, including winners for Clapton, then became stud-farm manager for the highly successful breeder Kirsten Rausing, at Staffordstown, in County Meath, from which, just before Alpinista’s triumph, he retired. Why a stud there? Because the land hasn’t been plowed since the 1840s and is rich in nutrients for the foals to feed on.

I’ve known Lloyd since schooldays, but hadn’t seen much of him. The first I knew of the appearance of his archive was from a zine he mailed out last year. It was printed on cheap paper, broadsheet-size, and contained some startling pictures. He had first picked up a camera at age 15, and he’d been inspired to look back at his archive by a box of negatives he discovered after his mother had died. She had kept them under her bed.

His pictures reflected nothing of the glamour or celebrity value of the world he had mingled in—they were simply excellent, original photographs, displaying a witty, compassionate eye, and a gift for composition. There are horses everywhere, even if they’re not present. There is the strangely moving Boxer, a shaggy pony in his last season, and a picture of Ronnie Wood, Jo Wood, and Denny Cordell, their eyes fixed on a horse Denny is muzzling and whistling to. There is the late Lord Harlech, son of David Ormsby-Gore, pictured fully integrated into the cowboy look of the Welsh border farmer, with keys dangling from his belt.

The masterpiece is a joint portrait of Lloyd’s wife, Victoria, and Penny Cuthbertson, wife of the late Desmond Guinness, co-founder of the Irish Georgian Society, photographed in a stable in rough country clothes. It could easily be a picture of two Polish women in the 50s—the point of the picture, its revelation, is the strength of their personalities, separate from their surroundings; their utter confidence and deadpan stare, as if a visitor had come to their village and asked them to pose for a picture.

Julian Lloyd’s pictures reflect nothing of the glamour or celebrity value of the world he mingled in—they are simply excellent, original photographs. And there are horses everywhere, even if they’re not present.

Lloyd had his one previous, small exhibition in London last year, which prompted the Tasmania-based curator and art critic Jane Rankin-Reid to write to Lloyd: “The photographic artists your work is naturally aligned with are as diverse as Bill Brandt (spacialist), John Deakin (hardboiled black eye), Evelyn Hofer (life settings, atmospheres), Michael Cooper (cultural naturalist) … add your favourites, honestly, you belong beside ANY great photographer you identify with.”

“Fifteen years ago, after we’d moved houses, I was surrounded by cardboard boxes full of loose negatives,” Lloyd tells me. “I thought, ‘What’s going to happen to these? Am I going to be leaving my children boxes of rubbish or put some format on them, have some coherent record of my life that will be usable, possibly of interest to a few people, even if only to my family?’ It turned into a long haul, the longest jigsaw puzzle on record, and I haven’t started on the color.”

James Fox is a London-based journalist, author, and a co-author of Keith Richards’s memoir, Life, and David Bailey’s memoir, Look Again