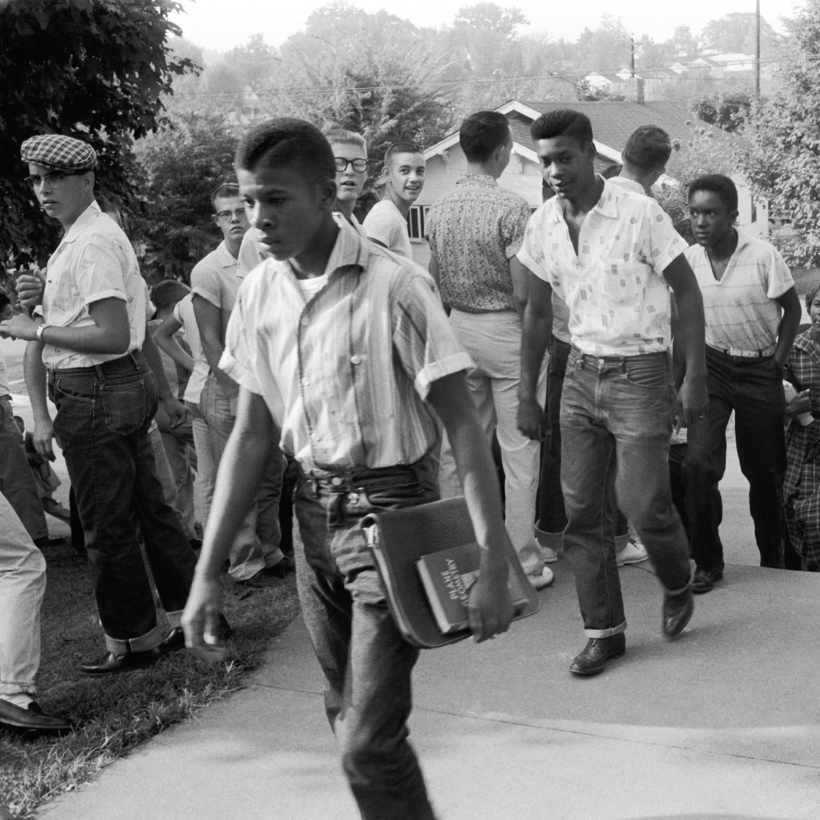

When I started graduate school, in 2006, I thought I had found the sort of project every Ph.D. hopeful dreams of: a story with obvious importance and intrinsic drama that no one else had written about. When Clinton High School, in Clinton, Tennessee, de-segregated, in August 1956, it was the first all-white school in the former Confederacy to successfully admit Black students following a court order. And then the town exploded. White rioters rocked the community. The governor sent in the National Guard, but he ordered the men to enforce the order rather than to block it. Eventually, the school was bombed and destroyed and, later, rebuilt by an international fundraising campaign headed up by the evangelist Billy Graham. Throughout all the turmoil, the school never closed, nor did it re-segregate.

What I didn’t realize as I began my research was that today schools in the United States are more segregated than they were in 1968, the year of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Instead of seeing how much my work could inform the modern fight to equalize education, I told others I wanted to capture the story before it disappeared. Partly that meant collecting oral histories with participants before they died, but I also believed the hate and vitriol that motivated the violence of 1956 was weakening. I wasn’t naïve enough to think society was “post-racial” (I am a product of the rural South), but surely open inequality was passé.

Unfortunately, elder millennials like me are the most de-segregated generation to pass through America’s schools. After Brown v. Board of Education, civil-rights advocates, federal agencies, and the nation’s court systems fought to turn the ruling into true educational equality for all students, altering the racial composition of many of America’s schools (though classrooms often remained segregated).

By the 1990s and early 2000s, many educators, white parents, and judges believed de-segregation had been attained. Local communities that had been under court supervision to ensure they maintained racial parity appealed to the judicial system, asking to have local governance returned to them. The courts complied, ignoring the ways that other forms of segregation had deepened in America.

Residential segregation in particular had become more entrenched. Researchers at U.C. Berkeley estimated that 81 percent of the nation’s metropolitan areas were more segregated in 2019 than in 1990. The increasing racial divide meant school systems could justify rising educational inequity as they returned to so-called neighborhood schools. By 2007, the judicial system had released 178 schools that had been under court-ordered de-segregation. That same year, the Supreme Court declared race was no longer a valid criterion for determining school assignments. School segregation doubled between 2001 and 2016.

Researchers at U.C. Berkeley estimated that 81 percent of the nation’s metropolitan areas were more segregated in 2019 than in 1990.

Back in 2006, my greatest worry was that my research and work would be for naught but the archives, that by the time I had finished both a dissertation and a monograph about the events at Clinton High, the story I was uncovering and reconstructing would have little relevance. Unfortunately, the opposite has occurred. That reality dismays me, though it no longer shocks me.

When non-academics chat with historians about the past, they often call upon a series of aphorisms that make the historians roll their eyes or cringe or get a gripe in their guts, depending on the topic and the speaker. And perhaps my story is making you think, “Those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it.” I would amend that saying: Those who do not change history will never break the cycle of inequality that scaffolds the United States’ civil, social, and political entities.

Our starting point should be this: heretofore, most Americans have chased after de-segregation, or the admittance of minority children into formerly white spaces. It is time for us to finally fight for integration, or the full elimination of discrimination based on color within our schools, neighborhoods, banks, businesses, municipalities, civic organizations, religious institutions, and cultural centers. I do not mean we should again bus Black children to white neighborhoods. I mean that Americans—particularly white Americans—must do the hard work of learning how to live with others in equity and justice. Until we do, Clinton High will remain a cautionary tale of just how close to the past we remain.

Rachel Louise Martin’s A Most Tolerant Little Town: The Explosive Beginning of School Desegregation is out now from Simon & Schuster